Contents:

Supporting a child with Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA) can feel daunting, but over my 15 years in secondary and post-16 classrooms, I’ve seen how the right approach can turn potential disruption into genuine engagement. It can be tricky, but it’s far from impossible. Once you learn to shift from demand to collaboration, everything changes.

PDA is a profile on the autism spectrum, defined by high anxiety and intense avoidance of everyday demands. Students may appear confident one moment, then struggle when routine expectations are introduced.

The first time I taught a student with PDA, I thought I’d completely lost control of my classroom. He was sharp, witty, and could debate me under the table about anything from Shakespeare to Star Wars. But ask him to write a paragraph… It took me a while (and a fair amount of humility) to realise this wasn’t about attitude or laziness – it was anxiety. The more pressure I applied, the faster the shutters came down. That experience completely changed how I understood behaviour in the classroom.

This article shares practical strategies, reflections, and advice on how to support a child with PDA in the classroom, helping you to reduce anxiety, build trust, and create conditions where students can genuinely thrive.

Understanding PDA

PDA is best understood as an anxiety-driven profile of autism. Students may:

- Resist everyday demands (even those they have chosen themselves)

- Use socially strategic avoidance and role-play

- Display mood swings or impulsivity when feeling pressured

- Develop strong fascinations, often focused on people

Avoidance in PDA isn’t deliberate misbehaviour – it’s a response to overwhelming anxiety. Students with PDA can be bright, socially motivated, and highly creative, but the routine pressures of school can make even small tasks feel monumental.

Examples of PDA in school

Students with PDA may show their anxiety-driven avoidance in a variety of ways, including:

- Refusal: A student might refuse to write an essay after initially agreeing to start, saying they “don’t know where to begin”.

- Control/sabotage: In group work, a student may take control or sabotage the process to avoid following someone else’s instructions.

- Withdrawal: During transitions, a student may withdraw or become oppositional, especially when moving between lessons, classrooms, or staff.

Understanding these behaviours as anxiety-driven avoidance rather than deliberate disruption is central to learning how to support a child with PDA in the classroom.

Why PDA can be disruptive in the classroom

In secondary and post-16 classrooms, PDA often looks different from other autism profiles. Students may:

- Appear compliant at first, then resist once a task begins

- Use role-play, negotiation, or humour to delay or avoid work

- Shift responsibility to peers or staff to manage anxiety

- Mask difficulties, making underlying anxiety invisible until it escalates

These behaviours can be misinterpreted as defiance or laziness. In reality, strict routines, high-stakes assessments, or tight deadlines can quickly escalate a student’s anxiety, causing avoidance or withdrawal.

Teacher tip:

Disruption often signals overload, not intent to misbehave. Reducing pressure, offering choice, and providing clear, structured tasks can transform potential disruption into engagement.

How PDA in school affects learning

Anxiety can make it hard for a student to concentrate. They may:

- Withdraw or avoid instructions and tasks

- Mask difficulties, which can make needs harder to identify

- Experience anxiety that impacts attendance and behaviour

Teacher tip:

Observe behaviour across different settings and collaborate with parents and support staff to identify triggers and patterns.

Implementing PANDA

The PANDA mnemonic from the PDA Society captures five key strategies that can help people with PDA. It isn’t a strict checklist, but a flexible framework to guide planning and interaction in ways that reduce anxiety and build collaboration.

Below are the five strategies, tailored to secondary classrooms – with real examples I’ve used:

- P – Prioritise and Compromise: Let go of non-essentials; hold firm where it truly matters.

Example: Choose three non-negotiables (e.g., safety, respect, deadlines) and be flexible on others. If a student says, “I can’t write now” I might respond, “Okay – do you want to talk through your plan first, then write?” - A – Anxiety Management: Use a calm tone, slow pace, and predictable routines.

Example: Provide a quiet starter activity while circulating, or say, “Take two minutes to organise your thoughts – no pressure.” - N – Negotiation and Collaboration: Work side-by-side, co-design tasks, and respect “no”.

Example: Ask, “Would you prefer to write the intro first or the evidence section?” Doing some parts together builds a sense of safety. - D – Disguise and Manage Demands: Use soft commands, suggestions, and indirect phrasing.

Example: Instead of “Write this now” try “I’m wondering where you might start.” Or write the prompt as a note: “Here’s something to think about…” - A – Adaptation: Change the plan as needed – Plan B, C, D.

Example: If the written task feels too steep, allow a mapping or bullet-point outline first. Or let the student present orally initially.

Embedding PANDA strategies into classroom practice

When I plan lessons now, I mentally cycle through PANDA. I ask:

- Which parts can I prioritise vs flex?

- What might raise anxiety in this lesson?

- How can I negotiate parts of the task?

- Where can I soften a demand so it feels less threatening?

- Where do I need to adapt on the fly?

That keeps me responsive, not rigid.

10 PDA strategies for teachers

Building on the PANDA approach and the idea of embedding flexible, anxiety-sensitive practices into lessons, here are 10 practical classroom strategies you can use day to day to support students with PDA.

- Build trust and reduce pressure

Establish a strong, trusting relationship.

Example: “I wonder if you could let me know what stage you’re at with this?” - Create a calm, low-demand environment

Minimise unnecessary pressures and maintain predictability.

Example: Break complex tasks into small steps and display them visually. - Focus on strengths and interests

Connect learning to the student’s passions or academic strengths.

Example: Let a student fascinated by gaming analyse narrative structure in a game storyline rather than a novel. - Adapt your language

Use calm, indirect, collaborative phrasing instead of commands.

Example: “Would you like to start with the introduction or the analysis?” instead of “Do this now.” - Support emotional regulation

Allow space for students to manage emotions and sensory input.

Example: Provide short ‘cool-down’ breaks, access to a quiet area, or stress-relief tools. - Be flexible and patient

Adjust expectations according to the student’s readiness.

Example: Permit extra time for assignments or verbal responses without penalty. - Offer choice and collaboration

Frame tasks as opportunities rather than demands.

Example: “We need to complete this task – would you like to begin with section A or section B?” - Make tasks clear and accessible

Use visual aids, schedules, or checklists to simplify instructions.

Example: Present numbered steps for a lab experiment, essay task, or group project. - Prepare for transitions

Give students warnings before changes in routine or staff.

Example: Announce five minutes before moving to a new lesson or group activity. - Work closely with families and professionals

Ensure a consistent approach across school and home.

Example: Agree on shared language for instructions and coordinate with teaching assistants, SENCOs, or educational psychologists.

Building on strengths and interests

Over the years, I’ve learned that if you can tap into a student with PDA’s interests, you’ve found the key that unlocks the door. These students often have incredibly strong passions – and while those fascinations can feel ‘off-task’ at first, they’re actually a bridge to learning. Building on strengths not only motivates but also boosts confidence and engagement. Students often shine when they have autonomy over how they explore a topic.

One of my most memorable GCSE students adored Doctor Who, but “Dickens is boring”. When studying A Christmas Carol, I let her analyse the 2010 A Christmas Carol episode – the one with flying sharks and Matt Smith. Slowly but surely, she was able to write fluently about Scrooge’s redemption. The difference was simple: the demand no longer felt imposed; it felt like her idea.

That’s the beauty of working with strengths – it reduces anxiety while building trust. It’s one of the most effective ways to understand how to support a child with PDA in the classroom. When a student feels seen for what they can do, not what they’re resisting, the whole dynamic changes.

It’s no longer teacher versus pupil; it’s two people solving a problem together.

Practical ways to build on strengths

- Integrating interests: Incorporate them into essay prompts, examples, or project choices.

- Autonomy: Allow students to choose how work is presented – written essay, podcast, storyboard, or slides.

- Leadership roles: Give responsibility in areas of competence, such as peer mentoring or digital tasks.

- Co-regulation: Use interests to calm anxiety; a short chat about a favourite topic before starting a demand-heavy task.

Teacher reflection:

Building on strengths isn’t about indulging avoidance – it’s about recognising that engagement is the first step towards independence. Once a student feels secure and competent, they’ll take more risks with learning.

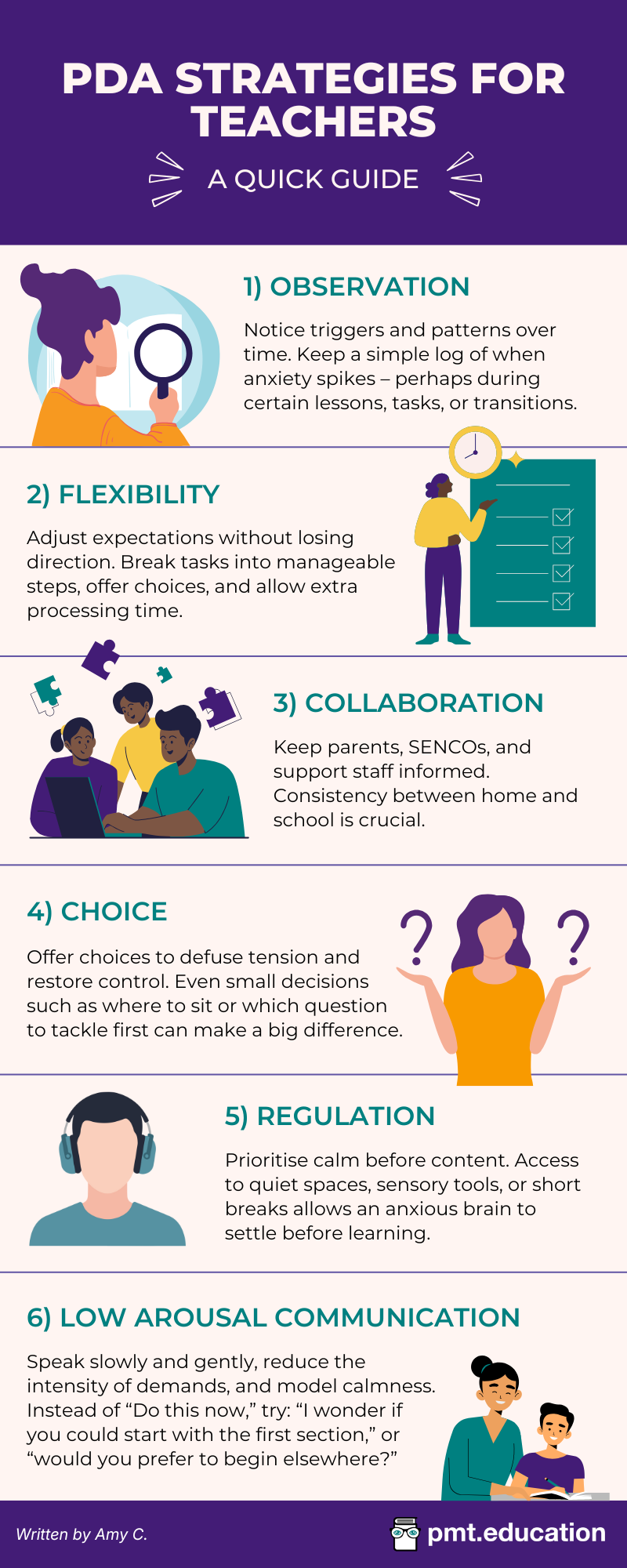

A quick teacher guide (infographic)

Supporting a student with PDA involves noticing subtle cues, adjusting approaches in real time, and maintaining consistency across adults.

The following infographic summarises PDA strategies for teachers that apply low arousal principles to help students engage effectively:

Teacher tip:

Think of it as setting the stage – lowering the emotional temperature so learning can happen. These small shifts in tone, timing, and structure are at the heart of how to support a child with PDA in the classroom and often have a bigger impact than a big speech about behaviour.

PDA strategies for teachers: Key takeaways

- PDA is anxiety-driven; avoidance is not deliberate.

- Flexible, collaborative approaches work best in secondary and post-16 classrooms.

- Focus on strengths and interests to engage and motivate students.

- Collaborate with families and professionals to maintain consistency.

- Build trust, reduce pressure, and provide safe ways to manage demands.

Supporting a child with PDA isn’t about lowering expectations – it’s about communicating, structuring tasks, and managing demands so students feel confident, engaged, and able to succeed. With patience, observation, and creativity, even the most challenging days can become opportunities for growth and achievement.

Further reading and support;

- PDA Society: What Helps Guides

- Fidler, R., & Christie, P. (2018) Collaborative Approaches to Learning for Pupils with PDA

- inTune Pathways: Understanding Equity-Seeking Behaviours in PDA

- Kristy Forbes: PDA Autistic Support (YouTube Channel)

Comments