Contents:

Over the years, education has seen certain ideas embed themselves in daily practice only to then be debunked, either as well-meaning but spurious or as having no solid basis in evidence.

As Carl Hendrick outlines in What Does This Look Like in the Classroom, learning myths often originate in one of two ways. First, they might come from initiatives or interventions that, as Hendrick suggests, ‘have no basis in research whatsoever’. Second, they might originate from poorly conducted research or evolve from a good idea that is rooted in evidence but, through iteration after iteration, becomes a distorted version of what it once was. This is what Dylan Wiliam describes as ‘lethal mutations’.

In this article, I’ll outline three especially prevalent EduMyths and for each one review some of the research that points to it being a myth:

- Learning Styles

- Cone of Learning

- Thinking Hats

Myth No. 1: Learning Styles

In many ways, learning styles are the archetypal EduMyth. The basic premise of learning styles is this: students are said to have a preference in the way in which they learn, typically visual, audio or kinaesthetic, and if the teacher matches their method of instruction to the preferred learning style, then the student will learn more effectively.

In effect, type X learners learn better doing X and type Y learners learn better doing Y. Paul Kirschner (2020) explains the theory in this way: “what we often hear is that we need to offer articles, videos and podcasts so that we accommodate people who learn better from reading, watching or listening. However intuitively right this feels, it’s untrue“.

It is important, though, to unpack the precise claim made by the theory of learning styles. The claim being made is not just that students have a preference as to how they would like content to be delivered, but also that matching teaching method to this preference will lead to better learning for those students. It is with the second part of the claim that we run into trouble.

It is almost certainly true that students do have a preference as to how they would like material to be delivered. Everyone is different, and so naturally, some might prefer to watch a video, read an essay or physically move around. However, there is no evidence to suggest that teaching in such a way that aligns with that preference will help that student learn better.

As David Didau outlines, it would make far more sense, even if learning styles were true, to match instruction to the content being taught. If you wish to teach a course on the Amazon river, everyone would almost certainly be best served by being shown a picture of the river, irrespective of any expressed preference. Equally, if you wish to coach the backhand in tennis, everyone is probably going to be best served (no pun intended) by having a go.

The danger comes when we limit instructional opportunity based on the belief X is better because of a presumed learning style. As the EEF concludes, “learners are very unlikely to have a single learning style, so restricting pupils to activities matched to their reported preferences may damage their progress”.

Myth No. 2: Cone of Learning

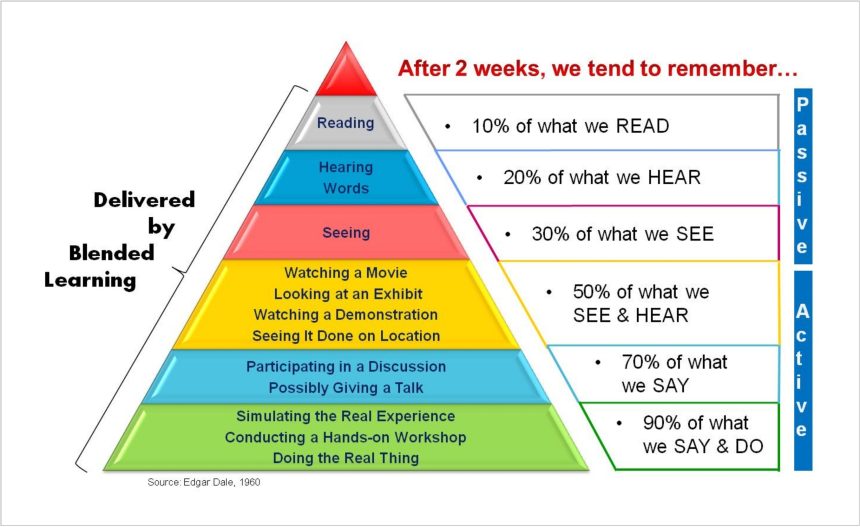

Dale’s Cone of Learning, sometimes labelled the learning pyramid, looks something like this, although there are many different versions:

Described as the Loch Ness Monster of educational theory, de Bruyckere, not one to mince words, labels this an out-and-out ‘fake’.

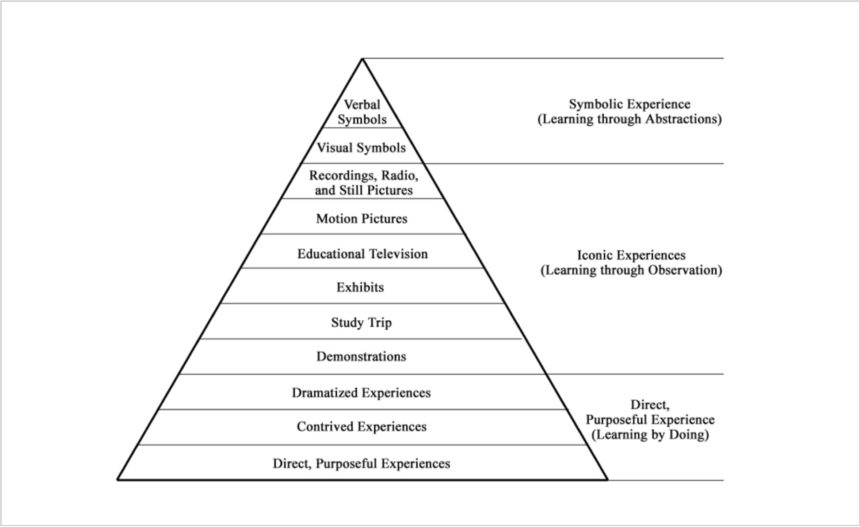

Whilst most often attributed to Edgar Dale, this is not strictly accurate. Dale’s original ‘cone of experience’ was published in the 1960s and was intended to suggest ways in which teachers might like to include audiovisual materials in teaching. It was not related to how much material people can retain under different circumstances. Dale also conceded and was quite open about the fact his original work was not based on any scientific research. It was simply a list of different audiovisual materials that might be incorporated into teaching, as below:

This is an excellent example of the ways in which ideas can be mutated into something they were never intended to be.

Myth No. 3: Edward de Bono’s Six Thinking Hats

Popular throughout the 1980s and 1990s and originating in de Bono’s 1985 book of the same name, ‘thinking hats’ describes an apparent way to adopt different modes of thinking and perspectives in order to better solve problems and facilitate discussion. One might, for example, literally or metaphorically don a red hat if one wished to try to focus or better coordinate an emotional response to a particular problem, a green hat to think creatively, or a yellow hat to promote a positive outlook.

The problem, of course, is that switching between modes of thinking is not as seamless a process as the theory appears to assert. One cannot suddenly hope to restrain their emotional responses in order, at an agreed time, to begin to think more critically.

As outlined by Dan Willingham, in order to think critically or creatively about a topic, one first needs to know a lot about that topic. Thinking critically is deeply entwined with the subject matter about which one hopes to think critically. In other words, it is very difficult to think with any precision about things we do not know. Yet, de Bono’s theory seems to suggest such thinking is a pose we could adopt if we so wished.

Comments