Contents:

Welcome to the AI-parenting age

If your child’s school report sounds less like a teacher wrote it and more like it came from a corporate manager, you’re not imagining things. Education has entered the artificial intelligence (AI) era, and it’s moving faster than most parents or schools can comfortably keep up with. Teachers have begun leaning on AI to survive the demands of the job: generating reports, planning lessons, and even whipping up assessments at speed. For those who use it well, this means better personalised feedback, lessons that are more timely and interesting, and more diverse assessments to check students’ progress.

On the other side, students are quietly outsourcing their homework to chatbots, using generative AI (GenAI) to write essays, solve maths problems, create flashcards and revision notes, and generate ‘original’ images and videos for assignments. Whether we like it or not, AI is now sitting at the virtual dinner table, wedged between your teen’s attention span and their WiFi connection.

Why AI isn’t just a modern calculator

In the 1970s, the arrival of the pocket calculator caused a stir. Parents and teachers worried that students would lose the ability to do mental arithmetic; that basic numeracy would erode under a sea of button pressing. However, a large body of research later disproved that fear.

A review of 79 research reports into classroom studies of students from kindergarten to high school predominantly showed that using calculators improved students’ algebraic processes and attitudes towards mathematics. Grade 4 was the only year where students showed a minor decline in ability compared to pen and paper use. Over time, calculators were integrated into lessons, teachers adapted their methods, and panic gave way to progress.

Now, AI is raising similar questions: will students stop learning if machines do the work for them? On the surface, this feels like a familiar debate, but there’s an important difference. With calculators, the concern was whether students would still practice core skills. With AI, one of the key concerns is whether students will even learn the right information to begin with.

Unlike calculators, large language model AIs such as ChatGPT don’t follow fixed logic. They generate responses using patterns in language—not facts—and sometimes produce confident but entirely incorrect answers. In technical terms, these are called ‘hallucinations’. These are not rare glitches; instead, they’re built-in limitations of how these models work. This means a student might get an answer that sounds correct, is structured like it came from a textbook, and even uses the right vocabulary, and yet be completely wrong.

For example, in my own experience of using ChatGPT as a physics teacher, it has on occasion invented formulas, misapplied scientific principles, or given false explanations, all wrapped up in perfect grammar. While doing research for this blog article, it invented citations and summaries of research articles that don’t exist, and presented this information with absolute certainty despite being challenged on it.

While these models are improving, they are ultimately trained on vast amounts of textual data scraped from the internet (up to a particular date), journals, and books. This also means that biases can inadvertently exist in that data, which is passed on to students. These models also operate as prediction engines that output information based on how it is prompted, often with a dose of bias towards being agreeable. In other words, if you prompt it with a particular bias, then it may output answers that further corroborate that bias.

These hallucinations then don’t just affect accuracy—they affect understanding. A student who repeatedly studies from AI-generated content may internalise misconceptions without even realising it.

AI and critical thinking

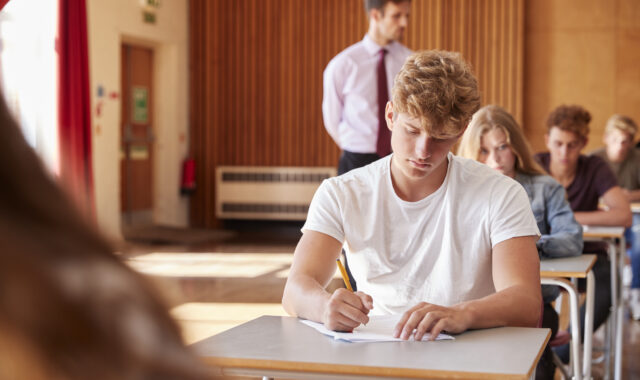

You may have come across the now-viral MIT study examining what happens in the brain when students use tools like ChatGPT to help with essay writing. In this four-session experiment, students who solely relied on AI to generate essays showed lower neural activity across key brain networks—particularly those involved in memory, planning, and internal focus. More strikingly, many of these students struggled to recall what they had written. When asked to summarise or elaborate on their essays, their responses were vague or uncertain. By contrast, students who started writing without AI and only used it in the final writing session retained better memory of their work, stronger engagement, and higher overall performance.

This research doesn’t stand alone—it further builds upon other recent findings about how AI use is reshaping the way students process information. Wecks et al. (2024) compared 193 students taking an introductory financial accounting course at a German university. They found that those who used GenAI for essay writing scored, on average, 6.71 points lower (out of 100) compared to non-users. More surprising perhaps was that the largest drops were seen in high-performing students, suggesting that AI may disrupt deeper engagement and critical thinking among students who usually excel. The authors particularly noted that how these students used GenAI, oftentimes by outsourcing their thinking, correlated with diminished exam outcomes.

A 2024 systematic review of 14 articles by Zhai, Wibowo, and Li also highlighted another concerning trend: overreliance on AI dialogue systems is more likely to see students disengage from metacognitive practices like questioning, reflecting, and refining their own thinking. Significant impacts of overdependence were seen on decision-making, critical thinking, and analytical reasoning abilities. The authors further highlighted that such dependence meant that for those students, the AI became a trusted voice, even when it was wrong, and that students stopped asking why or how.

Can AI feedback still support learning?

This doesn’t mean AI has no place in learning. Researchers at the University of Zurich released a pre-proof article in October comparing the effects of feedback from teachers, peers and AI. While this article may see minor corrections before full publication, its key findings are not likely to change. They uncovered an interesting phenomenon showing that students rated teacher feedback as harder to accept and less fair when compared to peer or AI feedback.

The study also examined students’ feedback literacy—the ability to understand, interpret, and use feedback to improve learning and performance—as well as having students revise their submissions based on said feedback. Students with higher feedback literacy rated teacher feedback as fairer and more acceptable. While all feedback sources used showed improvement in scientific argumentation, those with teacher feedback showed a marked increase compared to peer and then AI feedback. Although teacher feedback was best, all students improved. This included those with lower feedback literacy who might otherwise have struggled if they had only very in-depth teacher feedback to reflect on. These findings suggest that AI feedback could act as an intermediary.

While still in the early stages of research, these studies have begun to paint a picture: AI may be able to support the learning process, but it cannot replace the thinking behind it or feedback from an expert. When students rely too heavily on AI, outsourcing their thinking completely, they risk turning in well-structured work that hides a shallow understanding of the subject. Over time, this pattern doesn’t just affect grades; it gradually erodes their critical thinking and independent problem-solving skills. They lose the very abilities they’ll need to navigate complex problems, make independent decisions, and adapt in a fast-changing world.

Future-proofing your child’s career

As AI becomes more embedded in education and work, one truth is becoming increasingly clear: students who know how to think critically will be better prepared for the future. Whether your child ends up in a technical, creative, or people-focused profession, they’ll need to do more than generate content or solve problems with one click. They’ll need to question, problem solve, evaluate ideas, communicate clearly, and adapt when things go wrong.

Research from the World Economic Forum (2025) in their edition of the Future of Jobs Report gives insight into the 2025-2030 global labour market. Their data shows that across 22 industries, 86% of surveyed employers expect AI and information processing technologies to significantly drive transformation in their organisations by 2030. They further note how GenAI has received rapid uptake and huge investment across various industries, and that the demand for GenAI skills has increased accordingly.

These skills often consist of foundational GenAI skills and conceptual topics such as prompt engineering, trustworthy AI practices, and strategic decision-making around AI.

Practical applications, such as using AI to enhance efficiency or leveraging technology to develop applications, were also identified as important skills, as they allow businesses to leverage immediate productivity gains.

So, what does this mean for secondary school students who are likely to complete their university studies around 2030? They should expect AI to keep transforming industries, and for employers to prioritise skills such as critical thinking, adaptability, collaboration, and ethical reasoning. Interestingly, these are precisely the skills that can be eroded when students rely too heavily on AI to do the thinking for them.

But AI doesn’t have to replace thinking. It can support it if it’s used well. A growing number of studies show that AI tools, when paired with reflective prompts and human feedback, can scaffold learning and deepen understanding (Singh, Guan, & Rieh, 2025; Zhai, Wibowo, & Li, 2024). The key is teaching students how to use AI critically and intentionally.

To help, I’ve put together a simple checklist you can share and discuss with your child to help them make the most of AI without letting it atrophy the skills your child needs the most.

It still takes a human

In a world of fast answers, it’s clear that AI is here to stay and is being embedded in everything. What’s emerging is a hybrid future: one where AI offers speed and access, but people provide depth, context, and judgment. Thus, students still need to learn how to think critically for themselves. They need mentors who ask the hard questions AI can’t: ‘Why do you believe that?’, ‘How did you reach that conclusion?’, ‘What might you have missed?’ While AI can support the learning process, it doesn’t replace the nuanced guidance of a teacher, tutor, or expert; someone who knows the student, the pitfalls and misconceptions they may be prone to, and who can teach them to pause and think things through.

And yes, in case you’ve been wondering, this article was co-written with a GenAI language model. I used it to help gather research, summarise key findings, suggest rewrites, and challenge my thinking. However, rather than blind acceptance of AI suggestions, I drafted the outline alone, cross-referenced and read the research papers, and often pushed back on claims the AI was making. I iterated on my drafts, disagreed with the AI’s suggested sentence tweaks, discarded the bogus articles it invented, and naturally removed the vast majority of annoying em dashes (—) and other editing tidbits. I ensured this article is written with my voice and tone, carrying the message I want to convey.

This article is thus very much shaped by a human who has learnt what their own writing voice sounds like, and that’s the point: AI can be a brilliant assistant, but it still needs a critically thinking user to produce something meaningful.

An excellent article Latoya! You make some great points and reach an apt conclusion.